Gas geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean

Dear ladies and gentleman, my name is Cemal ASLAN. I was born in Lefkosa in February 1958. Im a senior petroleum engineer with 35 years experience in the oil and gas industry and also specialized in maritime law. Currently Im working at the BP's head office as an inhouse geologist.

Today Im going to present to you Gas geopolitics in the Eastern Mediterranean and my sincere thanks to you all

To advance its geopolitical position, a country might directly seek cooperation with other actors in its neighborhood. Alternatively, if it deems this approach impossible, it might choose to put pressure on the other actors first and then try to compel them to cooperate. There is, however, the risk that such a strategy might turn out to be counterproductive. Turkey seems to have chosen the second option in connection with its pursuit of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Eastern Mediterranean as a region in general and an energy region in particular is characterised by great volatility and extraordinary geopolitical instability. Conflict has traditionally been the norm, rather than the exception, and this greatly impacts its energy potential. Besides considerations of regional and global energy demand and prices, that are common to all extractive projects, the geopolitics of the Eastern Mediterranean means that this region faces further challenges with regard to the extraction, exploitation and export of hydrocarbons.

Additionally, new realities in the Eastern Mediterranean are characterised by radical current and emerging shifts in the international and regional landscape, and these of course also affect energy. The main parameters of these new realities are either directly or indirectly connected to the region, while others are independent of it but hold significant impact on the Eastern Mediterranean. Such realities have to do with issues in the EU and European states; transatlantic developments; changes in Turkey and Turkish foreign policy; and the Cyprus problem.

Political and energy developments in Europe impact Eastern Mediterranean gas projects in many ways. The abundance of gas in Europe and the challenging pricing terrain, combined with US supply and Russian reserves, mean that Europe may not for the time being be a realistic market destination for East Medeterranean gas in the short period.

While the member states of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum form a sort of regional alliance, Turkey’s estrangement from these countries might either further increase its desperation to gain leverage over the others or compel it to seek greater cooperation. It should also be noted that being party to the recently signed EastMed pipeline project by no means guarantees its success: the project’s viability remains uncertain and it should not be seen as the main measure of successful regional gas cooperation.

It seems likely that the natural gas can bring benefits for the entire region, even if Turkey has not found reserves in its waters yet. LNG regasification infrastructure has been quickly developed and can be used for importing more gas in the future, potentially also from other countries in the Eastern Mediterranean once sufficient political will and business justification align. This could help Turkiye to further diversify its gas import structure, which is a major energy goal for the country anyway.

For the last two years, Ankara has managed to reduce Russia's share by increasing gas supplies from Azerbaijan and utilizing LNG opportunities. Importing gas from the Mediterranean will help Turkiye diversify its portfolio. If priced correctly, Mediterranean gas could also increase Ankara's bargaining power with its current suppliers. Most importantly, Mediterranean gas can further Ankara's dream of becoming a regional energy hub. Turkiye has recently established a spot market for gas trading. The next step on the road to becoming an energy hub will be to extract gas from multiple regions, including the Mediterranean.

Europe is the ultimate target of Mediterranean gas. Despite decarbonisation policies, natural gas continues to find a place in Europe's energy basket. Diversifying gas imports is key to Europe's energy security, especially for EU members who depend on Russian gas. The European Commission is promoting the Mediterranean line as part of its Southern Gas Corridor strategy.

Export options

Over the past decade, regional states, energy companies and other stakeholders have explored different options for shipping natural gas to Europe. Most parties followed a hedging strategy, opting for simultaneous development of LNG and pipeline options.

LNG offers a flexible solution, enabling access to multiple markets without relying on transit states. However, the investment expenditures required for LNG are high compared to pipelines. The feasibility of LNG options for any individual producer at current reserve levels is debatable. One of the first proposals put forward in this context was to build a gas liquefaction plant in Israel, but was rejected due to environmental and some other concerns. Leviathan partners have explored the option of building a floating LNG plant, a high-tech but expensive solution.

In terms of pipeline options, two projects are on the table: the Israel-Turkey Pipeline and the Eastern Mediterranean Pipeline (EastMed). The Israel-Turkey Pipeline project is a solution that will connect Leviathan to Ceyhan in Turkey and serve the transition to Europe. Traveling a relatively short distance, this pipeline is the most cost-effective option for accessing the Turkish and European markets.

The EastMed pipeline is designed to directly connect the Mediterranean gas fields to Europe. This pipeline, which is approximately 1900 km long, also includes technical difficulties that increase the construction costs. Although the financial feasibility of the project is controversial, EastMed is supported by the EU and is considered a project of common interest but USA informs Israel it no longer supports East-Med pipeline to Europe. And also Washington informed Athens that they no longer support the East-Med project. The US no longer supports the proposed East-Med natural-gas pipeline from Israel to Europe, the Biden administration has informed Israel, Greece and Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus

Since Turkey and regional parties perceive conflicts from the perspective of regional balances of power as well as energy interests, it is difficult for the moratorium to produce a tangible result unless there is a direct effort to reduce political tensions. In this context, the most important development will be the normalization of Turkiye-Israel relations. This will create the most positive geopolitical impact in the short term, as it will alleviate Ankara's perception of exclusion and siege in the region. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that any lasting political solution in the Mediterranean must include a dialogue between Turkiye and Egypt and United Arab Emirates. Reconciliation between Ankara and Cairo is nearly possible under current circumstances, but both regional powers must develop mechanisms to effectively manage their rivalries.

Most export plans require extensive regional cooperation. Given that reserves are limited, it makes sense for producers to consolidate their reserves, build a joint export infrastructure, and collaborate to maximize the common good. In the absence of cooperation, most of the gas may remain on the ground or be traded only locally.

The tripartite alliance of Israel, Greece, and the Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus is supported by most Western actors as well as Egypt. Although they disagree on various issues, due to interest in the region’s gas reserves, they support Greece and the Greek part of Cyprus. The one-sided policy of the Western actors has caused severe dissatisfaction in Turkey. Also, due to the war in Syria, the Syrian government has not been able to conduct any exploration in the last decade, which has deprived Syria from gas resources in its territorial sea.

In addition, Lebanon has so far been unable to find an important source of gas. Thus, the triangle cooperation of Israel-Greece-Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus shaped a gas game and geopolitics that is supported by a strong block. Furthermore, the Eastern Mediterranean geopolitics has created a kind of geoeconomics in which the countries have chosen a zero sum game that has dangerous dimensions, and if this trend continues, dangerous events in the future would be inevitable.

This is also why many think that the region's energy potential will enable the resolution of political conflicts. According to the commercial peace logic of liberal international relations theories, natural resources should increase the cost of conflict and provide strong economic incentives to parties to resolve conflicts peacefully. Unfortunately, Mediterranean gas seems to have deepened the conflicts, let alone contribute to stability in the region.

While market conditions reduce the attractiveness of Mediterranean gas, political uncertainties in the region increase the risk. The main source of uncertainty is maritime jurisdiction and sovereignty conflicts in the region. In hydrocarbon exploration, some coastal states have opted to sign bilateral agreements to delimit the exclusive economic zones (EEZ). But to the extent that the different agreements signed contradict each other or violate the rights of third parties, they only deepen the conflicts.

Conclusion

With the anticipated improvement of Israeli ties to Turkiye in the aftermath of Israeli President Herzog’s visit to Turkiye, a pipeline to Turkiye – which possesses an extensive gas transport infrastructure and is dependent on Russian gas for 45 percent of its consumption – may seem possible. It is certainly desired by Turkey. However, strategic and economic considerations vis-à-vis the Hellenic allies (it is hard to visualize Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus and Turkiye cooperating) would seem to rule this out in the near term, as would anticipated Israeli wariness of undertaking long-term commitments to Turkey (such as a pipeline) in the early stages of their rapprochement. Instead, Israeli LNG sales to Turkey would be “bundled in” with Egyptian shipments, since Israel is currently dependent on Egypt for liquefaction.

Eastern Mediterranean gas is extremely significant – a "game changer” – for those states in or adjacent to whose waters it has been found. Israel, which was dependent in its first sixty years on semi-clandestine sources of oil to fuel its economic miracle, has become energy self-sufficient. Its gas surplus has enabled the creation of a fundamental and long-term tie with Jordan and Egypt, adding a “warm” underlayer to an often “cold peace.” Egypt has also attained energy self-sufficiency, and the gas industry will cement its position as the Eastern Mediterranean hub.

Gas has also created a wider interweaving of Egyptian, Israeli, Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus and Greece infrastructures and interests, which is one of the most notable geopolitical developments in the Mediterranean/Levant region in the past half century. Exports (and transshipment in the case of Greece) – especially of LNG – to Europe may become quite economically significant for these states, and even encourage additional infrastructure development of feeder pipelines and new liquefaction facilities. However, the marginality of Eastern Mediterranean gas resources in the greater global and European economy and geography of energy, as well as the long-term trend away from fossil-fuels in Europe, means that the significance and effect of Eastern Mediterranean gas will be limited primarily to those states, and perhaps Turkey and Lebanon in the future.

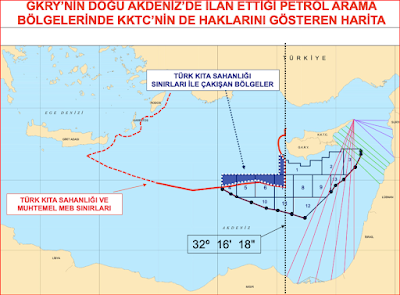

Turkey is strongly determined to respond to what it calls the “maximalist claims” of its neighbors in the Eastern Mediterranean and to a series of faits accomplis over the past decade that would ultimately affect its maritime influence in the zone if left unanswered. Given the sensitivity of the issue for Ankara, it might have been a miscalculation to assume Turkey would act with any less determination on this front than it has. Beyond this vital issue for Turkey, Ankara has strategic interests in Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and claims a historical responsibility to protect the Turkish Cypriot community in the island.

Therefore it maintains that Greek and Turkish Cypriots jointly own the island’s resources. It also objects to exploratory activities unilaterally undertaken off Cyprus’ coasts by what it calls the “Greek Cypriot Administration,” which, according to Ankara, is not competent to represent Cyprus as a whole. And, finally, Turkey does not want to be sidelined from future energy developments in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Comments

Post a Comment